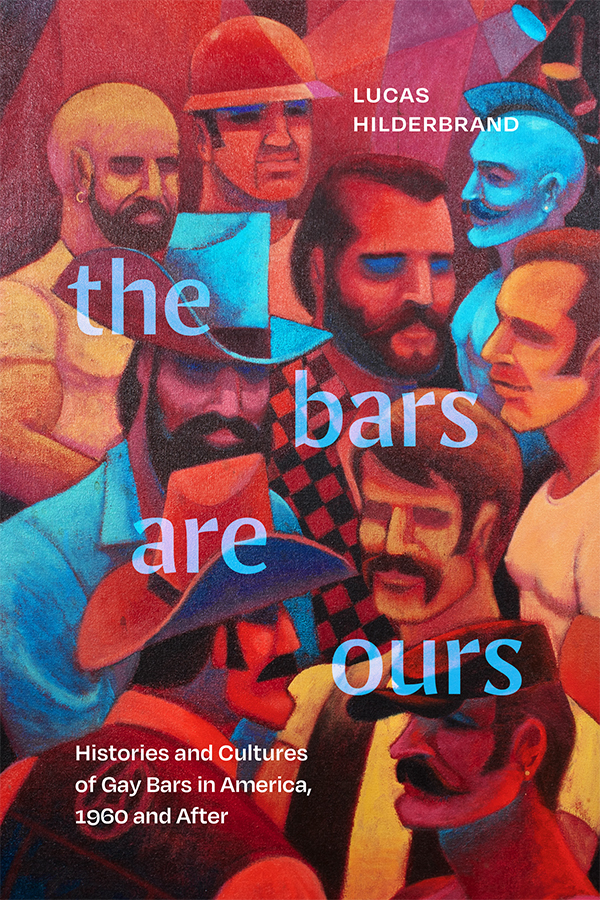

Lucas Hilderbrand is Professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Irvine, and author of Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright and Paris Is Burning: A Queer Film Classic. In his new book The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America,1960 and After, he offers a panoramic history of gay bars, showing how they served as the medium for queer communities, politics, and cultures.

Your previous scholarship is situated solidly in the realm of film studies. Why did you decide to research the history of gay bars, and how do you see your previous work informing your approach here?

Although my research trajectory may not seem self-evident to anyone else, it always made intuitive sense to me! Like everyone else, I’m a multifaceted person, and I’m as shaped by nightlife as I am by watching films and television or listening to music. My training in cinema and media studies helps me to understand the importance of popular forms that shape our culture, that become pervasive, that define the zeitgeist, and that may be ephemeral or fashionably cyclical—but that may not be taken seriously enough for other scholars to research. My interest often starts with realizing no one else has written about something that seems, to me, innate and central to our culture. Or it starts from discovering something fascinating in the archive that has been overlooked or that overturns my understanding of history.

I am also interested in challenging myself to learn new fields with each project. I’m not a traditionally trained historian, nor am I a social scientist. I try to be self-aware of what I don’t know and of how the questions I might ask offer new ways to make sense of bars’ cultural significance. To focus on zoning or liquor laws without also listening for what songs are playing, to my mind, would be to misunderstand how and why bars work for their patrons.

The Bars are Ours argues that gay bars were at the center of gay political and cultural formations in the second half of the 20th century. Has this changed today?

What has changed in the past 50 years is that the range of outlets to explore one’s queer identity and find community has expanded beyond bars or nightclubs, which were once the only public options. But I contend that nothing has truly replaced what bars provide.

LGBTQ+ community centers, for instance, started emerging in the 1970s to provide services; these developed after bar scenes were established and as an alternative to them. In the 21st century, online forums, social media, and dating/hook-up apps provide ways for people to connect. But the internet cannot replicate the experience of being in a shared public space. Community centers usually do not, and the internet cannot replace the experience of being on a crowded dancefloor as a part of a social body—or of making out with another person.

It is important to have alternatives that are not predicated on consuming alcohol or feeling pressured to consent to strangers’ gazes and touch. But for those who want to experience these things or who feel them as a rite of passage, bars are still the primary way to access them.

It’s also possible to be openly LGBTQ+ and even, in some cases, to feel safe holding hands with one’s partner in spaces that are not differentiated or defined as LGBTQ+ spaces; that did not used to be the case. But it’s still experientially and affectively different to be surrounded by straight people—even if they’re liberal allies—than it is to feel like one is in community.

Gay bars often are stereotyped as being a primarily white space, but you also write about bars that specifically cater to Black and Latinx patrons. How does race play into the history your book covers?

In LGBTQ+ culture and spaces, just as in straight ones, whiteness often goes unacknowledged as a default or norm—and this has the effect of reproducing white supremacist conditions. By the 1970s, activists recognized and fought back against conspicuously exclusionary door policies—both sexist and racist—and these efforts continued and needs to continue. Bars became the site to make visible and respond to bias in the queer community at large.

In part in reaction to discrimination at white venues and in part through self-determination, bars catering to Black or Latinx patrons have also opened and sustained these communities. These bars may feature more or less the same elements as white gay bars, but they also often foster community-specific cultures, ranging from favored musical genres to social norms. In some cities there’s a sufficient population to have multiple Black or Latinx queer venues, but in many places, there might just be one or none at all. I don’t know of any city where ethnically defined gay bars have reached parity with white bars, relative to local population demographics; even majority-minority cities typically have more white bars than non-white bars.

For my book, it was essential to me that my survey history be inclusive—that I understand Black and Latinx gay bars as gay bars. But I also recognized that they often had community-specific histories and cultures, which I worked to document as best I could without claiming to speak for or exoticizing them. The Atlanta and Los Angeles chapters, which center Black and Latinx venues, effectively decenter the white venues that may be the most famous locally and that have dominated understandings of their respective local scenes—for instance, Backstreet in Atlanta and The Abbey in West Hollywood. Similarly, I don’t focus on my local LA bar where I’m a regular: Akbar.

I also look to key parties where the goal was to produce integrated venues, or where clubs sought to serve multiple segments of the LGBTQ+ community by creating targeted parties on different nights of the week.

Are there any distinct differences between gay bars of the past and gay bars of today, and do you view these differences as being for better or for worse?

Before and into the early days of gay liberation, bars were often viewed as exploitative of gay people. They were often owned by the mafia or homophobic straight people, and they treated clientele poorly. Venues and owners were also vulnerable to shakedowns and raids from local vice cops. Queer people endured these indignities for as long as they did because they had so few alternative public spaces to congregate. In these venues, the management often pushed patrons to keep buying drinks in exchange for the right to occupy space. This had a correlative effect of exacerbating alcoholism at a time when many people were already prone to self-medicating their shame about their sexuality. Although these were gay venues, many venues also policed patron’s behavior so that people couldn’t dance together or touch casually.

We’ve moved beyond these conditions, obviously. But I also believe to only see past venues as bleak sites of oppression is reductive and inaccurate. If people hadn’t had fun and found kindred spirits, gay bars would not have endured and evolved. And people continue to experience a full range of tensions and release in bars of the present.

One of the challenges I faced for this book was trying to convey not only the facts of the past but also how it was experienced. One strategy I devised for this was to infuse the book with music; another was to draw parallels or contrasts from my more recent lived experiences.

How does the history of gay bars you relate in your book speak to our present moment of homophobic and transphobic fearmongering exemplified by drag bans and “Don’t Say Gay” bills?

Until recently, it was easy to slip into complacency about gay bars, to take them for granted or dismiss them as passé. Likewise, gay bars may not seem relevant to younger generations who came out before drinking age and who grew up with alternatives to bars—or who may reject binary understandings of gender and sexual identities. (Gay bars operate on a binary logic, in distinction to straight bars.)

What the resurgent culture war reveals is that our lives, our rights, and our venues remain precarious—and possibly subject to erasure. My book looks back on worlds and cultures we built, political battles we fought, and the ways we self-invented through bars.

Read the introduction to The Bars are Ours for free and save 30% on the paperback with coupon E23BARS.