Today we’re excited to present a guest post by Karl Schoonover and Rosalind Galt, authors of the new book Queer Cinema in the World.

Today we’re excited to present a guest post by Karl Schoonover and Rosalind Galt, authors of the new book Queer Cinema in the World.

In our new book, we attempt to reorient queer film studies away from a largely American and Eurocentric canon and toward non-Western forms of queer filmmaking that have increasingly been important for the circuits of world cinema and local queer politics. Here are ten queer films that we think you should see.

Dakan (Camara, Guinea, 1997)

Dakan is widely viewed as the first sub-Saharan African film with a gay theme. In it, Manga and Sori fall in love as high school students but are separated by their families. Manga’s mother sends Manga to a traditional healer to be cured of homosexuality while Sori’s father insists Sori take over the family business and marry. Sori does get married and has a child. Meanwhile, after years with the healer, Manga enters a relationship with Oumou, a white woman he meets through his mother. Both in some way outsiders, the two forge a bond. When the men see each other again in a bar, though, they immediately recognize their mutual desire. Despite their love for their families and apparently genuine relationships with women, Manga and Sori ultimately leave everything behind to be together. The film was controversial precisely for its direct representation of homosexuality, perceived by many African critics as un-African, sinful, or an unwanted relic of European colonialism.

Fish and Elephant (Li, China, 2001)

Fish and Elephant is often heralded as the first lesbian film from mainland China, but it does not tell a story of sexual awakening like so many other queer films from the period. Its protagonist Qun already knows she is gay when the narrative begins, and fending off her family’s expectations that she date men is a quotidian necessity. Qun and Ling do not simply refuse the dramatics of coming out of the closet; more than this, they refuse to serve as figures of the universality of queer identity or experience. At the same time, neither do they demonstrate the existence of queerness as a pre-existing local, indigenous, or non-Western formation. The best part of Fish and Elephant, though, is surely the amazing moment in which Qun and Ling ‘s mutual attraction is routed through the point-of-view of an elephant snuffling out sweet apples with her trunk. The film offers tactile and sensory pleasures at the same time that it locates nonhuman nature as part of the life world of queer humanity.

Funeral Parade of Roses (Matsumoto, Japan, 1969)

Toshio Matsumoto’s film combines documentary, narrative, and experimental form in an exuberant Oedipal melodrama set in the world of Tokyo’s “gai bois” or “queens.” Eddie is a young queen who works in a gay bar and travels in a mixed hippie scene of drug dealers, Marxist protesters, and avant-garde filmmakers. He is having a relationship with his boss at the bar, Gonda, and the film’s climax comes with the discovery that Gonda is the father who abandoned Eddie’s family as a child. Horrified by the realization, Gonda commits suicide, and Eddie blinds himself. Part of the film’s fascination is its combination of this melodramatic plot with a close attention to the thriving gay scene in Tokyo, and its links to counterculture and radical protest. The film mixes its fictional narrative with documentary sections interviewing some of the film’s actors, as well as gay men on the street. Moreover, many of its actors are nonprofessionals discovered in the bar scene. This self-reflexive mixture of documentary and fiction recapitulates the narrative’s move between underground scene and public performance—so that the film is always asking its audience to consider social and intimate relations as a question of inside and outside.

Futuro Beach (Aïnouz, Brazil, 2014)

Karim Aïnouz’s Futuro Beach testifies to an experience the director calls “queer diaspora.” The film begins in the Brazilian beach city of Fortaleza, where the lifeguard Donato is unable to save a drowning German tourist. After breaking the news to Konrad, the dead tourist’s friend, the two men begin a relationship that eventually takes Donato away from his family to live with Konrad in Berlin. Though following the lives of gay men from the global south to the center of Europe, Futuro Beach resists world cinema’s more Eurocentric and heteronormative impulses in its intense sensitivity to the alternative resonances of queer time and space. Focusing on gesture and bodily movement, the film evokes a powerfully affective sense of queer relationality as Donato and Konrad move in and out of alignment. And while queer bodies have the potential to remake subjectivity, the space between Brazil and Germany is equally crucial as a material, emotional and geopolitical fracture with which these characters must reckon.

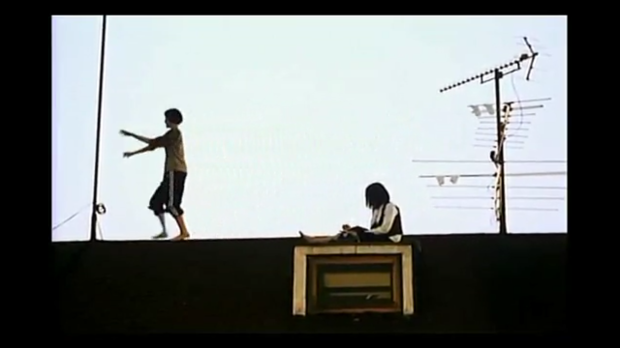

I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone (Tsai, Taiwan/Malaysia, 2006)

In I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone, homosocial proximities gradually become homosexual intimacies, but that transition is unremarked upon diegetically. As the narrative develops, the protagonist Hsiao-Kang also begins a sexual relationship with a woman, and his bisexuality goes equally unremarked. There is something of the bathetic here in the sense that the queer does not operate as a force of the revelatory, the climatic, or the confessional, and instead is commonplace. The film de-emphasizes its unfolding of Hsiao-Kang’s choices of sexual objects and locates sex as equivalent to quotidian acts of human survival, like peeing, walking, and food gathering. In one of its most visually striking shots, the three lovers float through the frame on an old mattress, embracing in an affectless polyamorous tableau. The film’s staging of the precarious lives of transnational migrant laborers in Kuala Lumpur places sexual acts in an unremarked category. The mattress speaks as much of their squalid living conditions as of their sex acts, and it has already played a narrative role when Bangladeshi migrant workers use it to rescue Hsiao-Kang after he has been beaten up and left for dead on the street. The very ground of sexuality—the physical object on which the lovers lie—speaks vividly of economic precarity and cross-cultural solidarity and care.

The Iron Ladies (Thongkongtoon, Thailand, 2000)

The Iron Ladies tells the true story of a mostly trans (in Thai terms, kathoey) volleyball team who became Thai champions. The heterogeneity of contemporary gender dissidence in Thailand is vividly staged in the film which, in putting together its volleyball team of outsiders, represents genders across the modern Thai spectrum. These kathoey players are both specifically Thai and, through sport, engaged with the world. Instead of an East–West logic that pits Western imperialism against conservative nativism, The Iron Ladies nests the national inside the global. Moreover, its strategy for constructing extra-national modes of identification is to engender a queer popular. The moment when the institution’s sexism and transphobia is revealed and the audience start cheering in support of the Iron Ladies is a feel-good cinematic coup that leverages the generic pleasures of the sporting underdog in order to champion queer publicity on a world stage.

Memento Mori (Kim and Min, South Korean, 1999)

This popular Korean horror film takes place in an all-girls secondary school, borrowing from the potent homosocial mises-en-scène of both queer classics such as Mädchen in Uniform and mid-twentieth century exploitation cinema, such as the single-sex boarding school or women’s prison. The intimacy between two girls––Hyo-shin and Shi-eun––comes to a head when they hold hands in the middle of class and, when violently punished, kiss on the mouth. When Hyo-shin commits suicide, her ghost returns to haunt the school. The disjunctive spaces and times brought on by her ghostly presence results in a formal and narrative intricacy that is as aesthetic as it is suspenseful. As living characters are pulled more and more towards the apparitional, their initially clandestine desire goes dangerously public. In other words, Memento Mori transforms the key generic elements of the globally popular East Asian horror film (longing, dystopic melancholy, surreal but extreme violence) into lesbian drama, making the genre suddenly seem inseparable from same-sex desire.

Proteus (Lewis and Greyson, South Africa/Canada, 2003)

Proteus is co-written and directed by South African filmmaker Jack Lewis and Canadian filmmaker John Greyson, and thus embodies an unusual cross-cultural queer collaboration. The film takes place in eighteenth-century South Africa and is based on archival records of a sexual relationship between a Khoi herdsman Claas Blank and a white Dutch sailor Rijkhaart Jacobsz when the two men were imprisoned on Robben Island. The film is noteworthy as the first gay-themed film made in South Africa after the end of apartheid. But rather than providing a conventional historical drama of gay life in the distant past, it proposes a queer approach to the passage of time and our relationship to what came before us: temporality and historicity are mutually imbricated in a disjunctive elaboration of cinematic time. The film uses visual anachronism to fracture time and to link colonial exploitation with apartheid-era incarceration and with the present day. It insists that systems of words and images often violently shape the world, but also that queerness leaves powerful traces.

Tropical Malady (Apichatpong, Thailand, 2004)

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Tropical Malady unsettles typical logics of modernity and folkloric belief, desire and its object, and what it means to be human in a beautifully queer tale of two boys and a tiger spirit. The film is constructed as a diptych, a film made of two distinct parts. The first section tells the story of a soldier, Keng, who is stationed in the rural north of Thailand. He meets Tong, a local boy, and the two embark on a romantic relationship. When Tong walks off into the jungle, he leaves Keng to an exhilarating but melancholic motorbike ride through the town on his own. Shortly after this encounter, the film flickers and vanishes, the screen goes black for thirty seconds, and the image returns with what seems to be a credit sequence for a different film, called A Spirit’s Path, about a shape-shifting Khmer shaman. In the second part, the same actors may or may not be playing the same parts. Maybe-Keng goes into the jungle to find Maybe-Tong, and in the almost complete darkness of the jungle, he encounters a magical tiger who may or may not want to consume him. Visual and narrative opacity are combined with a mysterious erotics of the shamanic were-tiger: by allowing himself to be eaten, Maybe-Keng can enter the shaman’s world.

The World Unseen (Sharif, UK/South Africa, 2007)

When the Dubai International Film Festival rejected Shamim Sarif’s film about lesbian love in early 1950s South Africa, the organizers said it was on the grounds that “the subject matter doesn’t exist.” The film’s evocation of an Apartheid past proved incompatible with its representation of sexual intimacy between two women. The World Unseen’s main character is Amina, an Indian South African woman whose progressive attitudes toward gender and race as well as her butch style mark her as out of sync with the other characters in Apartheid-era South Africa. Her romantic attraction to Miriam centers a web of untimely intimacies, in which the women explicitly reject hierarchies of race and gender. The film uses conventional tropes of the heritage film both to foreground women’s desire and to counter that genre’s more conservative impulses. The World Unseen refuses to make apologies for imagining something that conventional history would dismiss as impossible: a same-sex and interracial love in this particular time and place.

Use coupon code E16QCIN to save 30% on Queer Cinema in the World by Karl Schoonover and Rosalind Galt.

One comment